Prishtinë, 25 May 2017

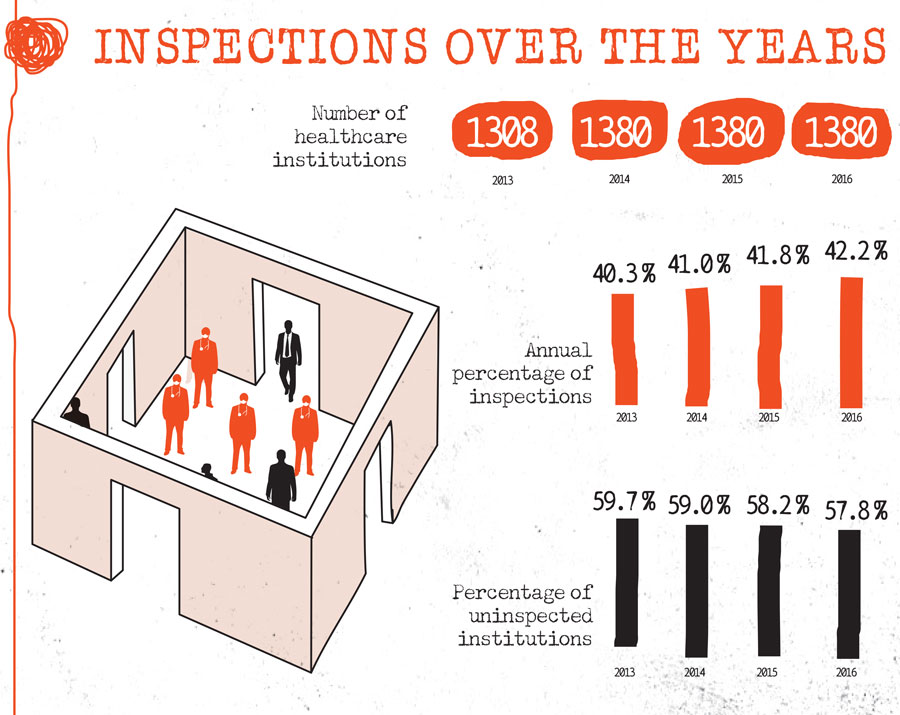

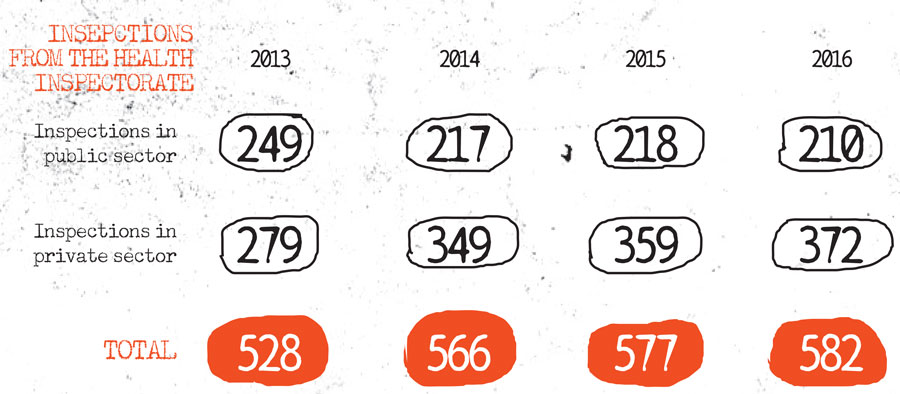

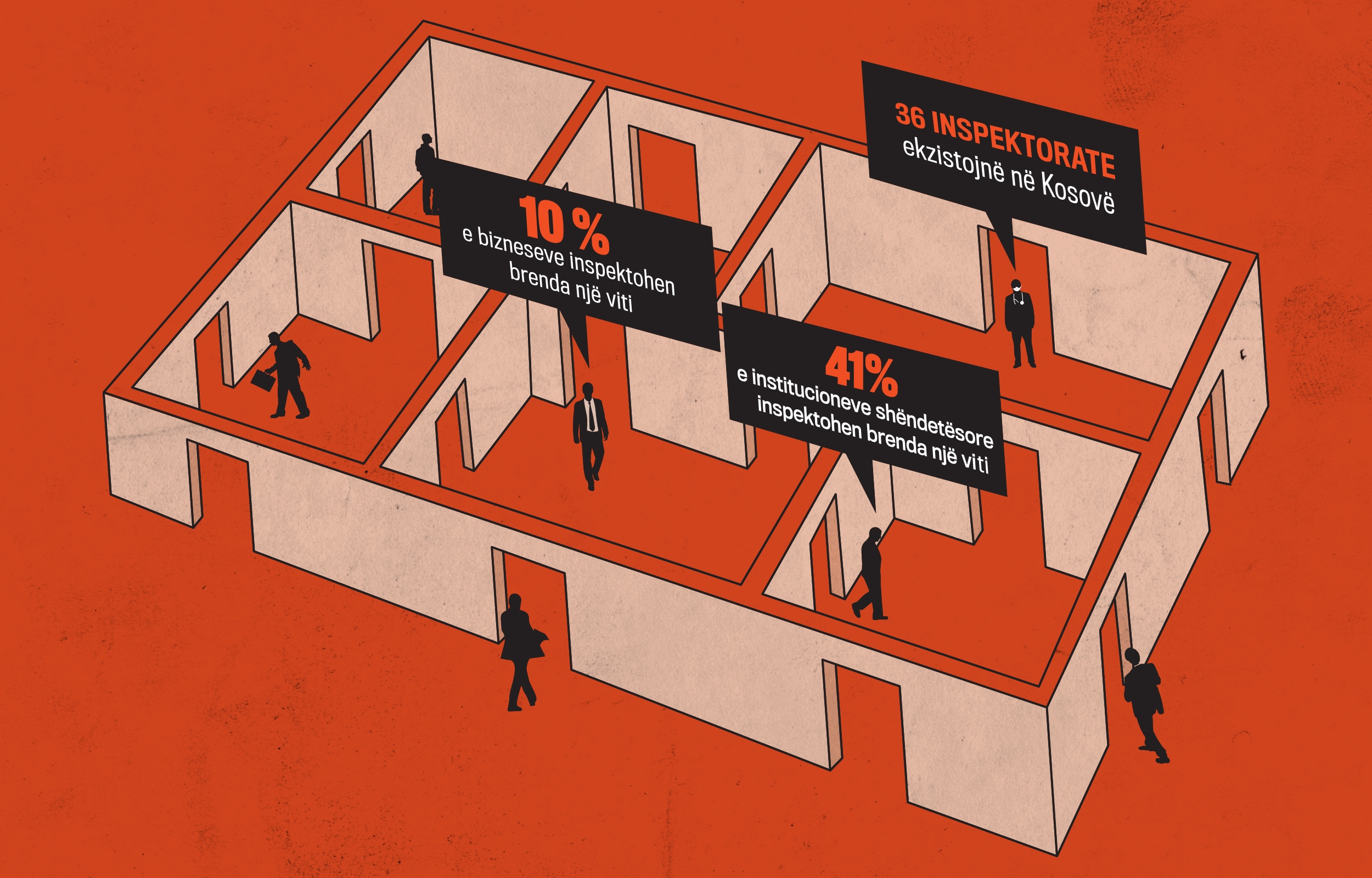

In Kosovo there are tens of inspectorates that are obliged to inspect different areas. The number of inspectors continues to be low, while the number of businesses and institutions that they have legal obligation to inspect has been growing throughout years. In this situation, inspectors manage to carry out few inspections, while citizens bear the consequences.

Around 61.3% of Kosovo youth aged 15-24 work without contracts, most of them are not paid for extra hours, and they do not enjoy elementary rights. Also, we are witnessing many scandals of private health institutions carrying our illegal activities throughout years, also proved by court verdicts. Environmental damages involving destruction of forests and rivers are at high levels. These and other vital issues are regulated with laws, while the oversight and implementation of these laws falls under the responsibility of these inspectorates.

In Kosovo, a considerable number of inspectorates was established in 2006. Despite the fact that in terms of competences inspectorates are at high hierarchical level, Preportr research found that inspectorates did not produce concrete results in the field of implementation of laws, since their very establishment until today.

The main obstacle is their chaotic functioning and organization. They are spread throughout special institutions such as ministries, municipalities and other independent institutions.

As a result, their accountability is also not concentrated. They generally report to their respective institutions. Most of these reports are for internal use only and they are not made public. Those that are, however, public are part of the reports of their respective institutions, and not classified as the work of the inspectorates.

Lack of reporting of their work in media and in some cases lack of work of inspectorates made the citizens generally hear about them only in cases of corruption affairs, which considerably undermined their reputation.

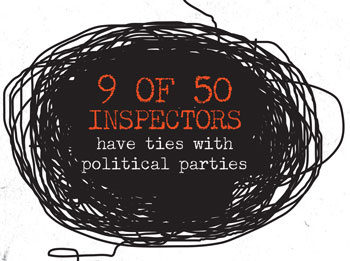

During its research, Preportr found that media reported about circa 35 inspectors accused for "Abuse of official duty, for illegal acquisition of assets", with three head inspectors and one regional coordinator involved.

Poor organization of inspectorates complicated the identification of their number and their type. In many websites of institutions there are no inspectorates as special sectors. In order to see whether there is an inspectorate for a certain field, one should look into laws regulating that field in order to see whether inspectorates are mentioned there.

In 2014 GAP Institute published a report on the functioning of these institutions and identified around 20 of them. According to researcher Visar Rushiti, there is a big variety of organization and functioning of inspectorates and there is no special central body that would oversee their work.

"Somewhere there are organized as divisions, while in other places we find them as departments, and as inspectorates. For example, the CEO of the Inspectorate within the Ministry of Justice reports to the Secretary, and then to the Minister. In other places, the inspectorate is an executive body. For example, Labor Inspectorate, where the head inspector responds directly to the Minister," explained Rushiti.

According to the Information Office of the Ministry of Trade and Industry, there are currently 26 inspecting bodies in central and local institutions covering all fields of work.

Preportr particularly focused on the Labor Inspectorate and Health Inspectorate, since these have the biggest influence on citizens' lives. The aim of this research was to present the problems which these inspectorates face in their work, as well as the lack of functioning or obstacles in their work in general, by analyzing their work and their activities.

Law on Inspections, not Inspectorates

There is no special law for inspectorates, a law which would set certain principles related to their work and their functioning. Inspectorates were established according to the necessity - some through decisions and administrative instructions, and others though laws. This type of organization is not efficient in practice. As a consequence, there is a need to initiate a special law that would regulate legal basis and hierarchical organization of all inspectorates in Kosovo.

In 2013, Kosovo Government stipulated the drafting of this law in its Legislative Program, but according to Information Office of the Ministry of Trade and Industry, there were no further steps taken in this direction. As a result, a new law is being drafted only for inspections.

"Currently we are preparing a Concept Document for Draft Law on Inspections, which would address the need in its entirety for the reform of inspection system in Kosovo, including both legal and organizational/structural aspect. We are working so that this draft law is completed during 2017, and in this process we are closely cooperating with World Bank. This inspection reform was budgeted in 2017 Budget Law," was the response of this Office for Preportr.

"Currently we are preparing a Concept Document for Draft Law on Inspections, which would address the need in its entirety for the reform of inspection system in Kosovo, including both legal and organizational/structural aspect. We are working so that this draft law is completed during 2017, and in this process we are closely cooperating with World Bank. This inspection reform was budgeted in 2017 Budget Law," was the response of this Office for Preportr.

According to them, Kosovo Government is fully informed about the current situation in the field of inspection, and this is the main reason behind this process, that we call the reforming process.

But Visar Rushiti from GAP Institute believes that the Law on Inspections would only deal with principles or inspection work, and not with their organization or functioning. According to him, the Law on Inspections should not substitute the Law on Inspectorates

"Draft Law on Inspections was opposed by the very Inspectorates because it contains provisions that harm the work of Inspectorates, such as informing the subjects before going to inspect them, which undermines the role of the Inspectorate. We have also opposed this law and proposed to have a model similar to Albania and Croatia, where there is a special law and a special body for all inspectorates which manages and oversees them." said Rushiti.

According to him, such a law would empower the role of the inspectorates, it would increase their responsibility and have a direct effect on the improvement of level of implementation of laws.

LABOR INSPECTORATE

Labor Inspectorate inspects only 10% of businesses

Each and every day, there are reports on the violation of workers' rights. The most serious problems have to do with the establishment of work relations, respectively work contracts. Labor Law, among others, stipulated the regulation of work relations between employee and employer in both public and private sector, setting out duties and responsibilities of both parties. Lack of contracts produces many consequences for employees, starting from their suspension, without previous notice, lack of care in case of injuries, lack of holidays, no payment for extra hours, etc.

According to the data from "Labor Force Survey" which is carried out by Kosovo Statistics Agency and published at the end of January 2017, 30% of employees in Kosovo work without a contract.

"the percentage of employees aged 15-24 working without contracts is 61,3%. When asked if they enjoyed their rights in their primary work, i.e. benefits from social security scheme, only 2,8% of the respondents gave positive answers," says this report, among other things.

Also, Policy and Advocacy Center (QPA) in August 2016 carried out a survey related to work contracts in the region of Pristina. In service, catering and trade sector 38,46% work without contracts, while in construction as much as 59,76% work without contracts.

This research indicates that construction workers work extra hours. 40,24% of the respondents declared that they work 50 hours a week, while as much as 14.63% declared that they work up to 60 hours a week. Despite the extra hours, some of these workers said they were had not been paid for those hours. 41% of the respondents said they had not been paid their extra hours.

Some of labor contest are being reviews in Kosovo courts. According to Kosovo Judicial Council data, Kosovo courts had 3,669 cases related to labor contests. 2,488 cases were unresolved as of January 1, which means they were transferred from previous years, while 1,181 new cases reached Kosovo courts.

Out of this total number of cases in process (3,669), 105 cases have to do with dismissal from work, 732 cases have to do with return to work place, 2398 cases deal with material compensation to the injured party, and 434 cases deal with other labor contests. Kosovo courts started this year (2017) with 2.387 unresolved cases of labor contest.

All these violations are happening while there is a Labor Inspectorate in place, which is an executive body and functions within the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare.

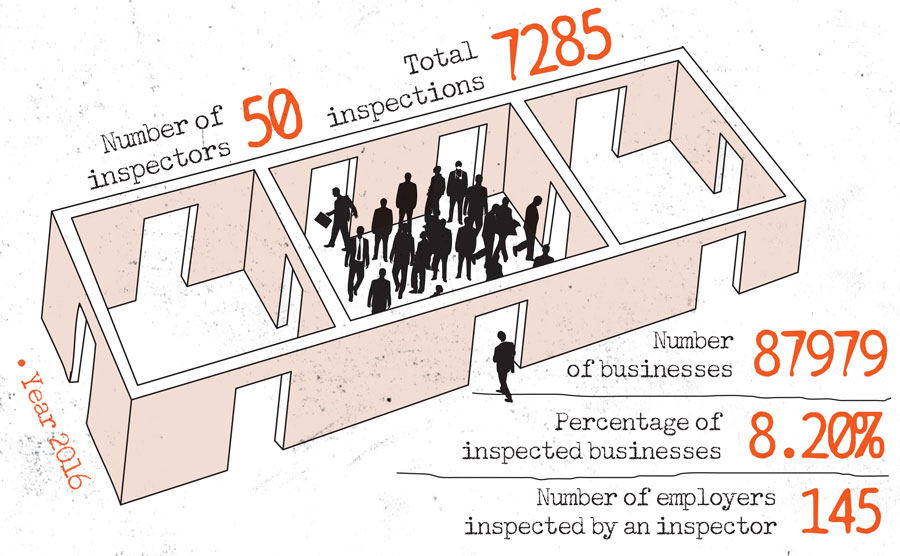

This inspectorate employs 50 inspectors, which are responsible to carry our regular inspections. on daily bases as well as if deemed necessary. Considering the low number of inspectors and their dynamics of work, very rarely do these inspectors knock on employers’' doors in order to inspect them. Some of these inspections have even been subject to indictments, dissatisfaction and suspicions related to possible favoritism towards some employers and consequently produced unfair decisions.

Between 2011 and 2016 Labor Inspectorate carried out between 6 and 9 thousand inspections. In 2016 this inspectorate carried out 7,285 inspections, out of which there were 4,997 regular inspections, 1,717 repeated inspections, 456 upon request of the parties, and 115 joint inspections. Consequently, if we look at all types of inspections we conclude that the total number of inspections also includes repeated inspections, which means that Labor Inspectorate does not manage to inspect regularly even 7,000 employers.

According to Kosovo Tax Administration data, there were 87,979 active businesses in Kosovo in 2016. Preportr took the total number of inspections during 2016 and compared it to the number of active businesses. This comparison shows that Labor Inspectorate managed to inspect only 8,2% of the total number of businesses in the country. More than 90% of businesses in Kosovo are not inspected. These data were calculated only for the private sector, since the inspectorate is obliged to carry out inspections also in public institutions.

If we consider only the private sector, one labor inspector during a year should inspect not less than 1,759 businesses. According to 2016 data, one labor inspector managed to inspect only 145 businesses during the year. According to these data, it turns out that in order to inspect all businesses, an inspector would need a total of 12 years.

The 2016 inspections carried out by this inspectorate found 1340 employees without contracts. During these inspections, 855 remarks and 128 fines were imposed against employers. These data also indicate that there have been violations of workers' rights, and if there were more inspections in place, more such cases would probably be evidences.

The head inspector of this inspectorate, Basri Ibrahimi, told Preportr that there are different breaches of Labor Law and that the most frequent violations have to do with work without contracts, work during night, work during official holidays, etc. He says that despite the low number of inspectors, in recent years the implementation of Labor Law marked progress. According to him, this inspectorate needs additional 130 inspectors in order to produce more effect in terms of implementation of Labor Law.

"An inspection per day per inspector is enough, but even this is difficult to achieve because there are many procedures to be followed prior to carrying out an inspection. Not only the private sector but also the public one takes much time, because there are many procedures. Public sector inspection takes much more time than private sector," says Ibrahimi.

The primary goal in the methodology of Labor Inspectorate is to educate and not punish. When breaches of workers; rights are identified, the employers first receive a note, and then they are given a short period of time in order to address the issues. So, an employer is always given a second chance. But considering the low number of inspectors and inspections as a result of that, this measure may not be effective, since employers first wait for this note. This method can produce little effect, when we consider that our inspectorate manages to inspect only 10% of employers per year. So, other employers who are not yet inspected do not feel at risk in case of breach of law, because they know that they would first receive a note, and they could potentially carry out with those breaches of workers' rights.

"We have been dealing with this issue for many years. We have tried different inspection methods, but we found that this is the best method. We believe that sanction is not enough, and employers should see us as partners, and not as a punitive apparatus," says head inspector Ibrahimi.

Inspectors do not treat cases properly

Policy and Advocacy Center (QPA) monitors Labor Law since 2011. Milaim Morina from this organization says that during these years of monitoring, they concluded that Labor Inspectorate is not sufficiently efficient in inspecting employers.

"The thing that worried us was the methodology of inspections, or the way how inspectorate targets businesses to be inspected. This is important because there are businesses who were inspected three times within a year, while there are large businesses that were never inspected in a 4-year period. We asked to have access to the list of inspected businesses, but we were denied such a thing," says Morina.

Jusuf Azemi, head of Independent Union of Small Businesses and Crafts told Preportr that in their field work they evident many violations of workers' rights, and they send this cases to the inspectorate, but this institutions does not undertake any measure to address these cases.

"We have had cases when we went to a company and found it with no work contracts. We have asked them to produce contracts within two weeks, and they did not do so, because they had the support of the inspector. When we told them we would publish the case in media, the very inspector together with the employer worked all night long and the next day they produced contracts," says Azemi.

He says that if there are so many workers with their rights violated every day, why should there exist a Labor Inspectorate, adding that the situation is even worse in construction and technical service sector.

In relation to this, head inspector Ibrahimi says that there is no well-organized private sector union, and that such declarations have no grounds.

But neither Kosovo Journalist Association (AGK) had nice experience with Labor Inspectorate. The president of this Association, Shkelqim Hysenaj, said that only during 2016 this inspectorate received 10 cases of journalists related to violation of their labor rights.

Nebil Mjeku is from the Municipality of Obiliq. In 2009 he was elected as municipal member of assembly. In June 2011 he got employed as labor inspector. He kept the two positions simultaneously. He also run during 2013 local elections as PDK candidate for municipal assembly member.

Nebil Mjeku is from the Municipality of Obiliq. In 2009 he was elected as municipal member of assembly. In June 2011 he got employed as labor inspector. He kept the two positions simultaneously. He also run during 2013 local elections as PDK candidate for municipal assembly member. "There is neither an assessment of sectors that are at a higher risk, which would contribute to an adequate planning. According to our analysis, construction is among the sectors with the highest risk and the most serious consequences, and thus its inspection should be of high priority compared to other sectors", says the report.

"There is neither an assessment of sectors that are at a higher risk, which would contribute to an adequate planning. According to our analysis, construction is among the sectors with the highest risk and the most serious consequences, and thus its inspection should be of high priority compared to other sectors", says the report.